Following the recent legislation in Oregon to decriminalize all drugs and other states like neighboring Arizona voting to legalize recreational marijuana, the focus in New Mexico has turned once again to the state’s policies in regard to illicit substances. Some are hopeful for a future with a harm-reduction approach as the beginning of the end of the war on drugs.

“It’s the start of a new era,” a University of New Mexico student familiar with illicit substances, who requested to be referred to as AJ to protect his privacy, said.

As psychoactive substances — like cannabis and psychedelics — are decriminalized at the state level, legalization advocates and some medical experts are hopeful more clinical research on the potential benefits these substances have will follow.

“More research could be done on certain substances that people initially thought were harmful, but are actually not as bad and could be helpful to society,” AJ said, referring to his goal in pursuing a career in psychedelic-assisted therapy. The practice was legalized statewide in Oregon earlier in November.

According to UNM psychiatry professor Rick Strassman, who pioneered psychedelic-assisted research and therapy in the 1990s, the increased accessibility legalization affords is a nuanced issue.

“You’re going to be increasing accessibility of potentially harmful compounds to people who may have no understanding of what they're taking or why … But on the other hand, increasing accessibility to a potentially useful set of experiences is a good thing, so I think one ought to go in with eyes open,” Strassman said.

With increased accessibility and more empirical research, AJ — who was charged last year with a felony for possessing less than a gram of THC concentrate — said the stigma against substances and substance users will fade.

Oregon serves as a testament to the changing public perception of illicit substances and its consumers, which has dramatically shifted in the half-century since the war on drugs was officially declared in 1971. 67% of Americans believe the government shouldn’t prosecute individuals for using drugs, according to a 2014 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center.

In contrast, there was an even split in public opinion over mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses just 19 years ago, signaling a broad shift in the country’s failed public health policies regarding substance use.

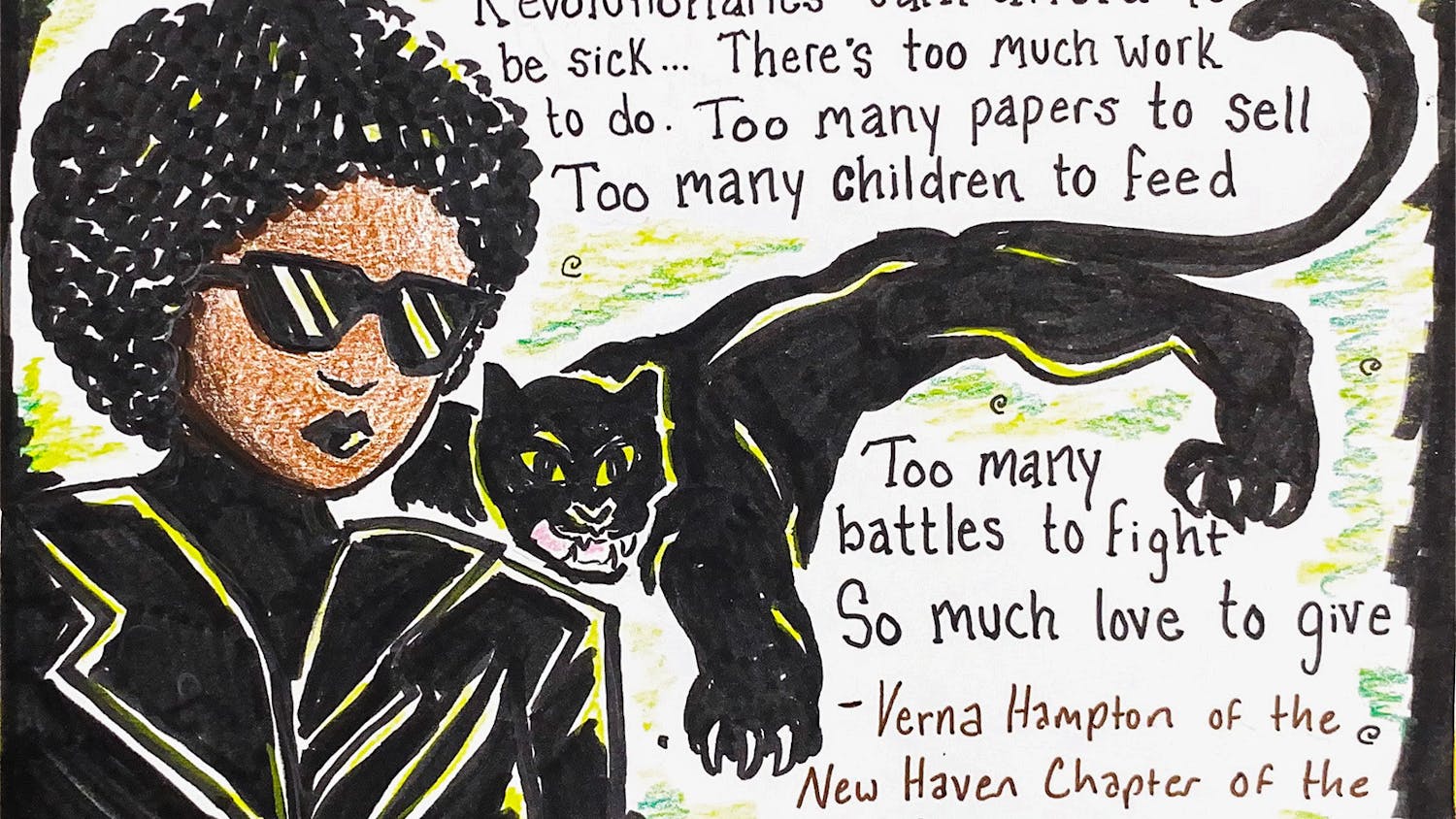

It’s increasingly recognized that the United States’ ill-conceived war on drugs — set in motion by former President Richard Nixon’s administration in the 1960s — has become a costly war indeed, both in terms of resources and human life. Disproportionate, devastating effects on Black and brown communities have been well-documented.

Though America’s war on drugs was exacerbated by Nixon and perpetuated by successors like Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, the demonization and over-criminalization of psychoactive substances took root in overtly racist rhetoric during isolationist-era America in the early twentieth century. It persists today as the criminal justice system discriminates against and disproportionately convicts people of color for drug-related offenses, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

“(The war on drugs) comes from a point of view that has no understanding of the problem,” another source, who requested anonymity to protect his identity from the lingering stigma surrounding substance use, said. “This is America — we tend to strong-arm everything, and of fucking course we’re going to strong-arm the problem at home and it’s gone terribly wrong.”

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

Incremental steps to unwind decades of punitive public policy are gaining momentum across the country, and Oregon’s decriminalization effort may come to be seen by historians as a turning point in the drug war’s tides.

“Oregon definitely became a model for all of us to look at other states,” Emily Kaltenbach, the director of the Drug Policy Alliance in New Mexico, said. “This really was a victory that took a sledgehammer to the war on drugs, and we expect that Measure 110 will set off a cascade of other efforts around the country.”

For Kaltenbach, one route New Mexico should consider is expanding and modifying the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) model to be more directly aligned to decriminalization.

A harm reduction program designed to keep “low level” substance users out of the criminal justice system, LEAD is meant to have law enforcement officers use “discretionary authority to divert individuals suspected of low level, non-violent crime driven by unmet behavioral health needs to community based health services.” According to the program’s website, LEAD is intended to “stop the cycle of arrest, prosecution and incarceration by addressing issues such as addiction, untreated mental illness, homelessness and poverty through a public health framework that reduces reliance on the criminal justice system.”

The upcoming 2021 New Mexico legislative session is also expected to contain new proposals concerning cannabis and other illicit substances.

Rep. Javier Martínez is spearheading an effort to legalize and regulate recreational marijuana for adults, the latest in a long line of attempts to permit recreational cannabis consumption in New Mexico. Similar measures have gone up in smoke at the hands of conservative lawmakers in recent years, but many of those lawmakers were ousted in the summer primaries and November election.

In the state Senate, Sen. Jacob Candelaria is seeking to “reform the criminal penalties we currently impose on people with addiction,” directly referring to New Mexico’s current policy of charging individuals found with residual traces of methamphetamine and heroin with a fourth degree felony. Candelaria said his legislation would mirror what Oregon has done in the past by defelonizing simple possession of any and all controlled substances to a misdemeanor.

“My legislation has more to do with ending and rolling back what has been and continues to be a racist war on drugs,” Candelaria said. “We know many of these criminal penalties were designed on the state and federal level to disproportionately affect Black, brown and Native communities.”

Gabriel Biadora is a beat reporter at the Daily Lobo. He can be contacted at news@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @gabrielbiadora