On June 24, the U.S. Supreme Court released their opinion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case. The opinion overturned both Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, two landmark cases which affirmed the constitutional right to an abortion. For people in every state across the country, including New Mexico, the decision raises questions as to the legality of abortion for where they live.

Abortion laws in New Mexico date back all the way to 1907 with the criminzalization of abortions performed after “quickening,” or when a woman would first feel motion from the child — generally around the fourth month of pregnancy. Abortion would be punishable under a charge of second-degree murder, according to Shannon Withycombe, an assistant professor of history who specializes in history of women’s health and reproduction.

The law could have been passed in an attempt to further support the argument that New Mexico should become a state, as it was repeatedly denied statehood mainly due to its large Hispanic and Native American population, according to Withycombe.

“I think it’s quite possible that this abortion (ban) was one of those things to be like, ‘Look, we’re just like everyone else … We are banning abortion, isn’t that another good reason to allow us into the Union?’” Withycombe said.

A subsequent law in 1919 altered the 1907 law, changing abortion to a felony punishable with a fine between $500 and $2,000. An abortion resulting in the death of the mother, however, would still be considered second-degree muder, according to an article from a 1970 issue of the Natural Resources Journal written by Jonathan B. Sutin.

With the 1950s, states throughout the U.S. began to retool their abortion laws to allow for “therapuetic abortions,” but these still came with their own roadblocks, according to Withycombe.

“(A therapeutic abortion) might be to save the woman’s life or to prevent any sort of illness or injury to a particular woman. But in most states, what they do is they set up these hospital boards. So a pregnant person has to appeal to this board … and prove to these — all white men, by the way — that their life or health is in danger. And, usually, the board said no,” Withycombe said.

New Mexico wouldn’t alter their law until 1964, however. The new law would establish “criminal” and “permissive” abortions. Criminal abortions would be punished as a second-degree felony and criminal abortions resulting in the death of the mother as a fourth-degree felony. A permissive abortion allowed abortions in the case of preserving the health of the mother in consulation with two physicians licensed in New Mexico, according to the Sutin article.

The problem with the 1964 law, to Withycombe, comes down to the physician input, leading physicians to rely on factors like their relationship to a woman’s husband or a woman’s race.

“They might actually say no to a white woman because, they’re like, ‘There’s too many non-white people in the state. We gotta start tamping down on that. We want white women to have more babies, so we’re not gonna let you have an abortion, but we will say yes to maybe, a Hispanic woman having an abortion.’ So both of those things could happen, depending on who those physicians are,” Withycombe said.

Shortly after the 1964 law was passed, a 1969 statute would expand the medical scope of permissable abortions, making it illegal for a provider to perform an abortion except in cases of rape, birth defects or to preserve the health of the mother, according to the Las Cruces Sun News.

This expansion to include more specific medical determinations, though, played into the other “trap laws” present in the statute — along with requiring accreditation for hospitals to perform an abortion, consulting physicians had to now work at a hospital and could not simply be licensed in New Mexico as with previous laws, according to Withycombe.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

Four years later, this statute would become unenforceable when Roe v. Wade was decided in January 1973. However, the statute still remained law and could have become enforceable again if Roe was overturned. In March 2019, there was an attempt to repeal the statute, but the bill failed in the House on a 24-18 vote, acording to the same Las Cruces Sun News article. There were no other attempts to repeal it until February 2021 in which Senate Bill 10 would pass into law, repealing the long-standing ban.

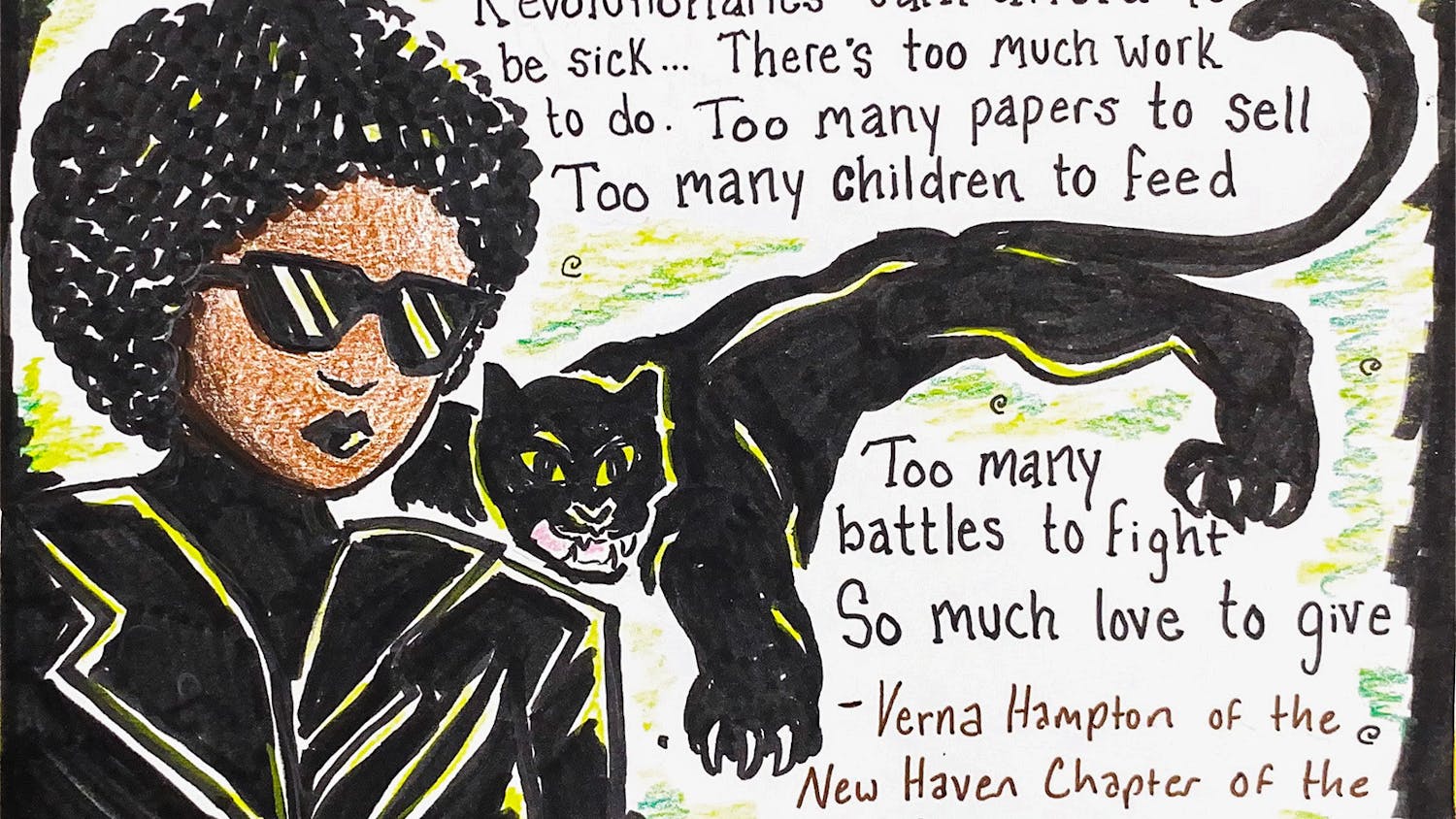

Historically, abortion bans have been linked to white supremacy and the supression of minority populations. New Mexico represents a unique position when looking at its bans through this lens, according to Withycombe.

“That argument didn’t reach the same levels in New Mexico. Not to say there’s no white supremacists in New Mexico; that’s not the truth. But, because there’s this much longer tradition of non-white people having high-placed political power positions, it doesn’t quite work the same way … I think that’s sort of in the background of all of these laws, actually,” Withycombe said.

The culture in New Mexico also represents a unique position for those in support of abortion. Withycombe specifically mentioned her time at other institutions and the difference of attitudes between students here and elsewhere.

“There is this sort of assumption, a much more quicker assumption, by people who live in New Mexico, that the person sitting right next to you is going to have a completely different life experience than you … So it’s sort of harder to push these laws in New Mexico … because New Mexicans are more liable to be like, ‘Well I don’t know what their situation is’ … Which is one of the reasons why some of these anti-abortion laws have not worked in the past decade,” Withycombe said.

No other legislation has come since 2021 to either affirm or restrict access to abortion in the state. On June 27, 2022, Lujan Grisham signed an executive order which prohibits the executive branch of the state government from cooperating in any investigations or legal actions surrounding abortion in the state and for the State Regulation and Licensing Department to “work with boards of professional licensure to protect abortion providers from out-of-state sanctions,” according to the Center for Reproductive Rights.

As a historian, Withycombe has studied the effects of abortion bans and emphasized that these types of laws do not reduce the need for abortions, but only increase the amount of abortion-related deaths. Withycombe also noted other reasons for these bans being passed.

“The first wave of criminalization of abortion that happened in the late 1800s was about sustaining white supremacy, and I don’t think we should ignore that this round,” Withycombe said. “As much as anti-choice people talk about this being about the life of babies, I think we have a lot of examples of how there’s all kinds of other legislation that you could pass that would actually help the life of babies once they’re born. Because those aren’t around, then maybe we need to look at other reasons why this (anti-abortion) legislation is being pushed and is successful.”

John Scott is the editor-in-chief at the Daily Lobo. He can be contacted at editorinchief@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @JScott050901